How Pore Size Analyzers Enable Breakthroughs in Catalyst and Battery Research

In the quest to engineer materials that power cleaner energy, faster chemical reactions, and longer-lasting technologies, understanding the microscopic architecture of porous substances has emerged as a linchpin of innovation. At the heart of this pursuit lies pore size analysis—a suite of techniques that maps the distribution, volume, and connectivity of pores within materials. Far from being mere measurement tools, pore size analyzers have become indispensable partners in advancing catalyst and battery research, unlocking breakthroughs that redefine what’s possible in these fields.

Decoding Porosity: The Unsung Hero of Function

Porous materials are not just empty spaces; they are dynamic landscapes where interactions between molecules, ions, and electrons unfold. In catalysts, pores act as nanoscopic reactors, controlling how reactant molecules access active sites and how products diffuse away. A catalyst with poorly tuned pore sizes might trap reactants or block product release, crippling efficiency. Similarly, in batteries, pores govern ion transport: too narrow, and ions face tortuous paths that slow charging; too wide, and the material may lack the surface area needed for stable energy storage. Pore size analyzers—ranging from gas adsorption-based methods like BET (Brunauer-Emmett-Teller) and BJH (Barrett-Joyner-Halenda) to mercury intrusion porosimetry and advanced techniques like positron annihilation lifetime spectroscopy—illuminate these hidden dimensions, turning guesswork into precision engineering.

Catalysts: Tailoring Pores for Precision Chemistry

Catalysis is the art of accelerating reactions while minimizing waste, and pore size analyzers are the cartographers of this art. For heterogeneous catalysts, such as those used in refining fossil fuels or synthesizing green hydrogen via ammonia decomposition, the size and distribution of mesopores (2–50 nm) and macropores (>50 nm) directly influence performance. Consider zeolites, crystalline aluminosilicates with uniform micropores (<2 nm): their ability to selectively adsorb molecules makes them ideal for cracking hydrocarbons. However, optimizing their pore size requires exacting measurements. Pore size analyzers reveal whether a zeolite’s channels are too constricted for larger feedstocks or if defects create unwanted dead zones. By correlating pore data with reaction kinetics, researchers can tweak synthesis conditions—adjusting template molecules or calcination temperatures—to engineer catalysts that boost yields by 30% or more.

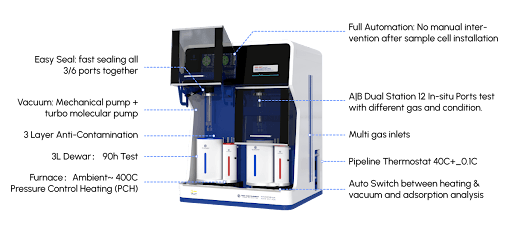

In recent years, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) have revolutionized catalysis with their tunable porosity. These hybrid materials, built from metal nodes and organic linkers, can be designed with hierarchical pores: micropores for molecular sieving and mesopores for rapid mass transfer. Pore size analyzers equipped with in situ capabilities (e.g., monitoring pore changes under reaction conditions) have been game-changers here. For instance, during methanol-to-olefins conversion, MOFs with optimized mesopores prevent coke formation by allowing bulky intermediates to escape, extending catalyst lifespan from hours to months. Without precise pore mapping, such design feats would remain theoretical.

Batteries: Engineering Pores for Speed and Stability

As the world shifts to electrification, batteries demand materials that balance high energy density, fast charging, and longevity. Pore size analyzers are critical to solving this trilemma, particularly in lithium-ion and emerging solid-state batteries. In conventional lithium-ion batteries, the electrode’s porous structure—comprising active material particles, conductive additives, and binders—dictates ion diffusion rates. If pores are too small, lithium ions struggle to navigate the tortuous network, causing voltage drops during fast charging. If too large, the electrode may lose mechanical integrity, leading to capacity fade.

Take silicon anodes, which promise 10x the capacity of graphite but swell by 300% during lithiation. Their porous architecture must accommodate this expansion without fracturing. Pore size analyzers, combined with X-ray tomography, reveal how pore networks evolve during cycling. Researchers use this data to design hierarchical porous silicon composites: macropores absorb swelling stress, mesopores facilitate ion transport, and micropores anchor the material to the current collector. Such designs have enabled silicon anodes to retain 80% capacity after 500 cycles—double the performance of earlier iterations.

Solid-state batteries, with their non-flammable solid electrolytes, face unique challenges: ionic conductivity depends on the electrolyte’s pore connectivity and size. Pore size analyzers help optimize ceramic (e.g., LLZO) or polymer electrolytes by identifying bottlenecks in ion pathways. For example, a study using mercury porosimetry found that reducing macropores from 1 µm to 200 nm in a garnet-type electrolyte increased ionic conductivity by 40%, bringing solid-state batteries closer to commercial viability.

Beyond Measurement: Enabling Cross-Disciplinary Innovation

The impact of pore size analyzers extends beyond individual materials. They foster collaboration between chemists, materials scientists, and engineers by providing a common language—quantitative porosity metrics—to align design goals. In catalyst research, this means linking pore structure to turnover frequency; in batteries, it bridges the gap between lab-scale synthesis and real-world performance. Moreover, advances in machine learning now allow researchers to predict material behavior from pore size data, accelerating the discovery of next-generation catalysts and battery components.

Conclusion: Pores as Gateways to Progress

Pore size analyzers are more than instruments; they are windows into the nanoscale world where chemistry and physics converge. By decoding the “architecture of emptiness,” they empower researchers to transform porous materials from passive supports into active enablers of efficiency, durability, and sustainability. As catalyst and battery technologies race to meet global decarbonization goals, these tools will remain at the forefront, turning pore-by-pore insights into breakthroughs that reshape industries and daily life.